Bioavailability refers to how much (quantity) and how quickly (rate) an active substance (drug) absorbs and becomes available at the target site in the body. [1] From another perspective, it is the percent of a substance that reaches systemic circulation. An intravenous injection (IV) has a bioavailability of 100%: the substance is injected into the bloodstream instantly and made completely available. So IVs get an A+ for bioavailability.

Non-hospital administration methods fall elsewhere on the curve. These include CBD/cannabis inhalation, nasal spray, transdermal applications, and oils/tinctures/edibles. These administration routes put obstacles in the way of absorption. In the case of oil-based orals, the hurdles are significant.

Cannabinoids & Bioavailability

Oral administration takes CBD/cannabis on a long journey. First, must navigate through the intestinal wall. Then they enter portal circulation, where they are beaten into submission (metabolized) by the liver. First-pass metabolism characterizes this great sojourn; at each stage, cannabinoids are rendered inactive and effectively useless. These inactive metabolites are then excreted by the kidneys… or simply wholesale. [2,3] But it gets worse.

From the start, cannabinoids were ill-equipped for the trip. The body readily absorbs water-soluble compounds. The water we drink boasts near 100% bioavailability. Cannabinoids are not water soluble. On the contrary, they are highly lipophilic, meaning they attract and dissolve in lipids/fats. Oil and water don’t play well together. Of course, the body does absorb lipids, but the process requires bile secretion and micelle formation. The result is that most cannabinoids cannot muster a sufficient rate of absorption before clearance.

Terrible absorption rates do not bode well for bioavailability:

- Oral THC bioavailability has been estimated at 4-20%. [2,4]

- Oral CBD bioavailability has been estimated at 13-19%. [3]

To put this in perspective, the bioavailability of THC inhalation has been estimated as high as 56%. [4] Average bioavailability from CBD inhalation has been estimated at 31 %. [3] Robust research is limited regarding bioavailability, especially in humans. Still, oral ingestion gets a solid D for bioavailability.

More on Tinctures

Tinctures represent the lion’s share of CBD products. [5] Tinctures aim to boost bioavailability with a simple instruction: hold the oil under your tongue for 60 seconds or longer. In general, the highly-vascularized tissue under the tongue (sublingual) is purported to afford 3-10 times greater absorption compared to simply swallowing. [6]

So What Stands as a Problem?

The problem is that available research (which is limited) suggests that bioavailability for oral cannabinoids does not significantly improve (statistically) with sublingual or oro-mucosal administration. [2-4, 6-8] Enhanced absorption from the sublingual route remains a hypothesis for cannabinoids. Perhaps this administration method extends to the upper range of the estimated oral bioavailability (19-20%). That is also a hypothesis!

Now we’ve discovered a sobering fact: oral bioavailability of cannabinoids is poor. On an A-F scale, we gave it a D.

But as Albert Einstein said, “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.” Fortunately, it’s possible to bend the reality of oral bioavailability.

Combining a high-fat meal with cannabinoids produces major improvements in bioavailability. Zgair et al (2016) observed a 2.5- to 3-fold increase in systemic exposure of THC and CBD when administered to rats with sesame oil (mostly long-chain triglycerides). [6] A 2019 study published in Epilepsia examined eight human patients; a high-fat meal prior to CBD capsules amplified maximum concentration 14-fold and area-under-the-curve 4-fold. [7]

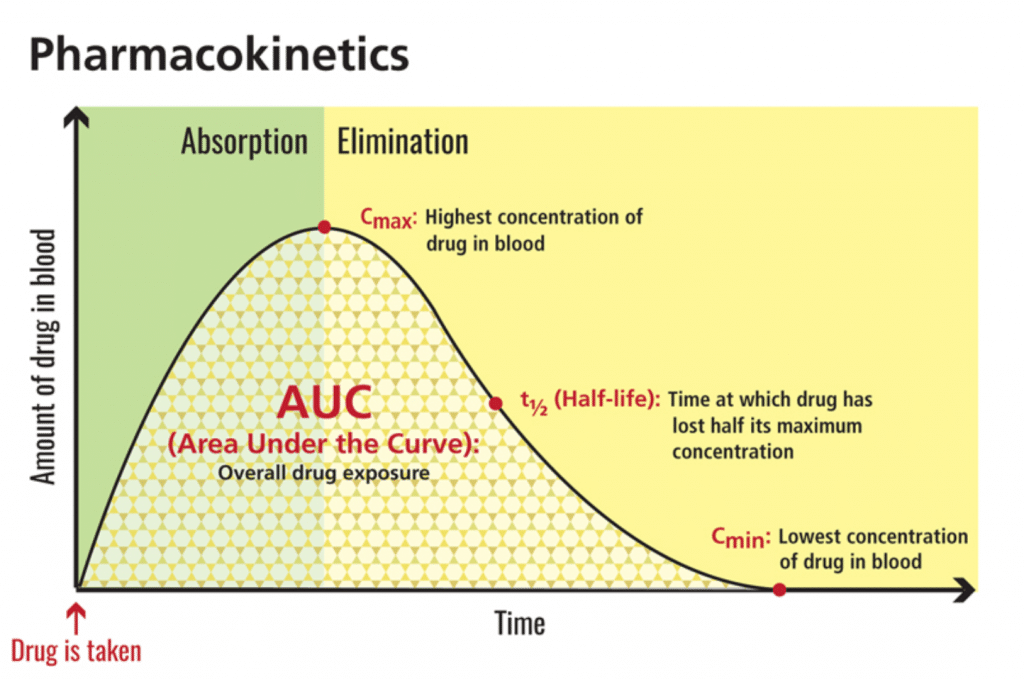

Maximum concentration, or cmax, refers to the highest amount of a substance (i.e., CBD) that reaches circulation. Area-under-the-curve, or AUC, reflects total exposure over time. In this 2019 study, CBD not only reached levels 14 times higher than fasted baseline — it also multiplied total exposure by four. [7] In terms of bioavailability, this is a big deal.

[Graphic 2: U.S. National Library of Medicine]

The FDA-approved CBD isolate drug Epidiolex® echoes this phenomenon. Look no further than the safety label: “Coadministration of EPIDIOLEX with a high-fat/high-calorie meal increased Cmax by 5-fold, AUC by 4-fold, and reduced the total variability, compared with the fasted state in healthy volunteers.”

This Bioavailability Graph Miracle

When ingested, fats are broken down and form chylomicrons (CM), or lipid-protein particles. These particles have strong affinity for cannabinoids. Cannabinoids jump on the CM bus, so to speak. Those that make it (an estimated 1/3) bypass first-pass metabolism. They enter circulation through intestinal lymphatic transport. [6] Instead of portal circulation and relentless pounding from the liver, these cannabinoids enter circulation through lymph. [8]

This is not the same as simply infusing cannabinoids in oil carriers. The purpose of extraction/ into fats is decarboxylation and solubility. Achieving peak CM levels appears to require significant fat content, such as that found in medium- to high-fat meals. [6,9]

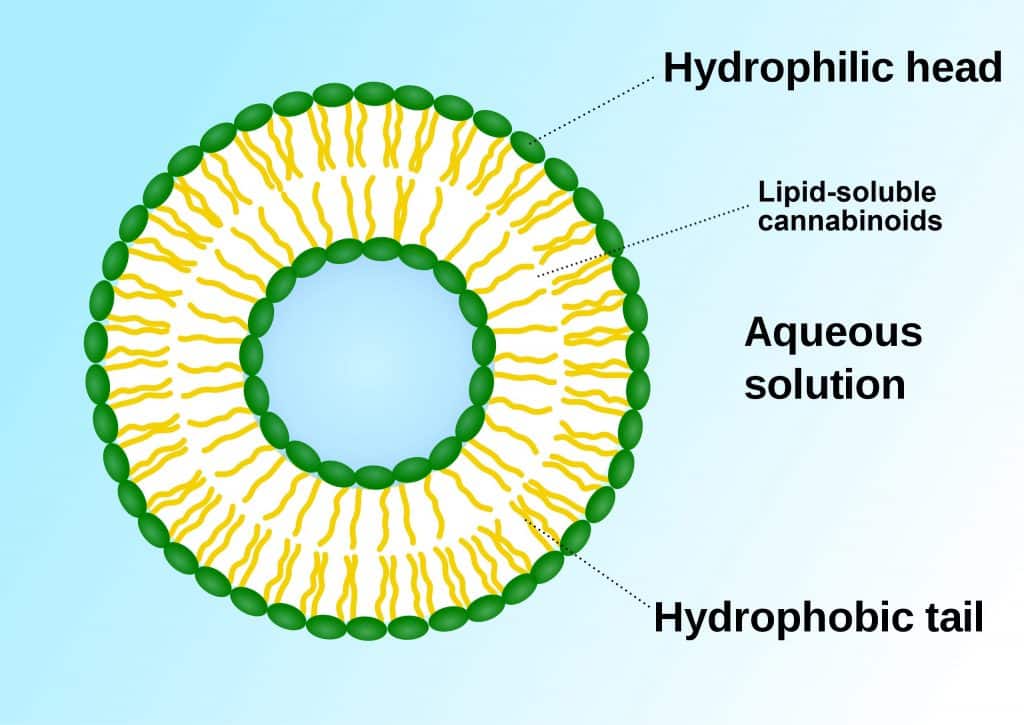

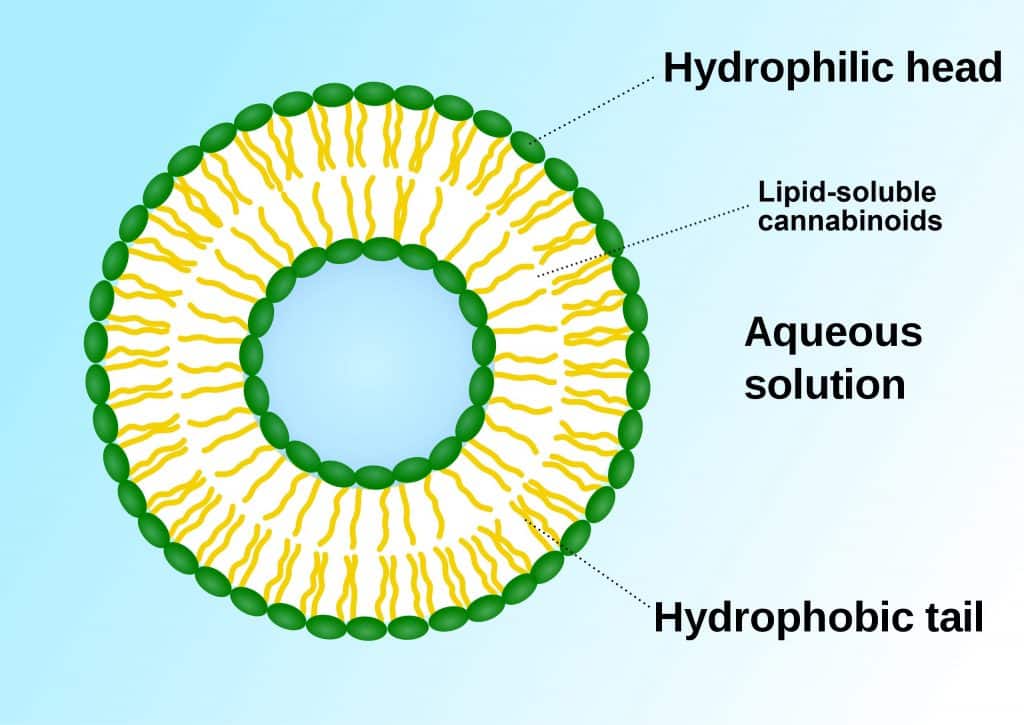

Another promising adventure concerns liposomal formulations. Liposomes are lipid nanoparticles that serve as carriers or transporters for a whole range of pharmaceuticals. [8,10] Essentially, they are phospho-lipid ‘bubbles’ capable of delivering encased lipids (e.g., cannabinoids) into aqueous solutions. This gives cannabinoids the surface appearance of being “water-soluble” although they are not.

[Graphic 3: SuperManu]

Remember, cannabinoids are fat-loving, water-hating molecules. The phospho-lipids in a liposome have hydrophilic (water-loving) heads and hydrophobic (water-hating) tails. The bi-layer (two layers back-to-back) means lipids can be trapped inside. Liposomes may thereby help protect cannabinoids from first-pass metabolism and increase rates of absorption substantially. It also appears that liposomes increase CM and lymphatic transport (like high-fat meals) although this mechanism of action is unclear. [8]

Recently, several companies have patented liposomal cannabinoid products designed to enhance absorption. Marketing that says ‘water-soluble’ likely relates to liposomes; cannabinoids are never water soluble, but may appear as such when encased in a liposome. Challenges associated with this technology include manufacturing difficulties (such as drug loading), variable stability, and cost. [10]

Final Word

The marketing surrounding cannabinoid products can be dizzying. Terms like enhanced absorption, superior delivery, and even water-soluble all point to bioavailability. Overall, bioavailability is how much of the cannabinoids we dose actually reach the bloodstream. Due to their lipophilic nature, oral cannabinoids receive a D in bioavailability. But a high-fat meal or liposomal technology can boost this grade up to a B. And that’s worth pinning on the fridge.

References

- Chow, Shein-Chung. “Bioavailability and Bioequivalence in Drug Development.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics,6, no.4, 2014, pp. 304-312, doi:10.1002/wics.1310. Journal Impact Factor = 1.75, Times Cited = 11 (ResearchGate)

- Mcgilveray, Iain J. “Pharmacokinetics of Cannabinoids.” Pain Research and Management, vol. 10, suppl. a, 2005, doi:10.1155/2005/242516. Journal Impact Factor = 1.685, Times Cited = 72 (ResearchGate)

- Millar, Sophie A., et al. “A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 9, 2018, doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01365. Journal Impact Factor = 3.831, Times Cited = 10 (ResearchGate)

- Huestis, Marilyn A. “Human Cannabinoid Pharmacokinetics.” Chemistry & Biodiversity, 4, no. 8, 2007, pp. 1770-804. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200790152. Journal Impact Factor = 1.449, Times Cited = 284 (ResearchGate)

- Corroon, Jamie, and Joy A. Phillips. “A Cross-Sectional Study of Cannabidiol Users.” Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research, vol. 3, no. 1, 2018, pp. 152–161, doi:10.1089/can.2018.0006. Journal Impact Factor = NA, Times Cited = 12 (ResearchGate)

- Narang, N. & Jyoti Sharma. “Sublingual Mucosa as a Route for Systemic Drug Delivery.” International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3, no.2, 2011, pp. 18-22. Journal Impact Factor = 4.773, Times Cited = 65

- Schoedel, Kerri A., and Sarah Jane Harrison. “Subjective and Physiological Effects of Oromucosal Sprays Containing Cannabinoids (Nabiximols): Potentials and Limitations for Psychosis Research.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 18, no. 32, Dec. 2012, pp. 5008–5014., doi:10.2174/138161212802884708. Journal Impact Factor = 2.412, Times Cited = 6 (ResearchGate)

- Karschner, Erin L et al. “Plasma Cannabinoid Pharmacokinetics Following Controlled Oral Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Oromucosal Cannabis Extract Administration.” Clinical Chemistry, 57, no.1, 2011, pp. 66-75, doi:10.1373/clinchem.2010.152439. Journal Impact Factor = 8.008, Times Cited = 94 (ResearchGate)

- Zgair, Atheer et al. “Dietary Fats and Pharmaceutical Lipid Excipients Increase Systemic Exposure to Orally Administered Cannabis and Cannabis-based Medicines.” American Journal of Translational Research, 8, no. 8, 2016, pp. 3448-59. Journal Impact Factor = 2.829, Times Cited = 14 (ResearchGate)

- Birnbaum, Angela K., et al. “Food Effect on Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol Oral Capsules in Adult Patients with Refractory Epilepsy.” Epilepsia, vol. 60, no. 8, 2019, pp. 1586–1592, doi:10.1111/epi.16093. Journal Impact Factor = 5.562, Times Cited = 2 (ResearchGate)

- Ahn, Hyeji, and Ji-Ho Park. “Liposomal Delivery Systems for Intestinal Lymphatic Drug Transport.” Biomaterials Research, vol. 20, no. 1, 2016, doi:10.1186/s40824-016-0083-1. Journal Rank = 0.828, Times Cited = 12 (ResearchGate)

- Zgair, Atheer, et al. “Oral Administration of Cannabis with Lipids Leads to High Levels of Cannabinoids in the Intestinal Lymphatic System and Prominent Immunomodulation.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, June 2017, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-15026-z. Journal Impact Factor = 4.525, Times Cited = 10 (ResearchGate)

- Bruni, Natascia, et al. “Cannabinoid Delivery Systems for Pain and Inflammation Treatment.” Molecules, vol. 23, no. 10, 2018, p. 2478, doi:10.3390/molecules23102478. Journal Impact Factor = 3.060, Times Cited = 3 (ResearchGate)

Originally: The Reality of Oil Bioavailability, V1, V2, 2019

![]()