The Spigot

The decline of music culture in the digital age.

Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy.

— Ludwig Von Beethoven

Why do I add music to the end of every post?

Discussions of musical evolution often reflect generational differences and evolving tastes rather than objective apexes or declines in artistic creativity or cultural value related to civilizational ascendancy or decay.

To reduce music, and indeed all art to “a matter of individual taste” is to ignore the wider implications of the collective consumption of culture and the powerful and connective experiences music in particular can impart to a society.

To deny a connection between the popular tastes of music in a given epoch, its evolution through different periods influenced by respective triumphs and turmoil, and the arc of ascendancy or decline of a given civilization would ignore obvious signs symbolically expressed lyrically or musically.

The quickening of cultural decline that seems to be the order of this era, is often expressed musically as decadence, debauchery, nihilism, and moral decay. But if recent history is any barometer, there is a specific point in time that appears to have ushered in the decline of popular music, and it may be connected to several emerging techno-social phenomena related to musical production, distribution, and consumption.

Before we trace those lines toward that point, let’s first explore some historical patterns to gain some evolutionary insights that might offer both clarity and perspective.

The rise of popular music across the West, from the great classical music of Europe from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, to the rise of Blues, Jazz, Rhythm and Blues and Rock & Roll in the United States and Britain, signaled an evolving and transformative artistic apex that, a few lulls and voids excepted, consistently delivered profound emotive auditory experiences at a cultural level.

The relation of art and culture to the rise and fall of civilizations is well documented. In the panorama of history, music, art, and architecture have not merely been expressions of culture, but have also mirrored the spirit of their times, often heralding the rise or signaling the decline of civilizations.

The enduring pillars and temples of Ancient Greece, epitomized by the Parthenon, stand as testaments to the zenith of a civilization dedicated to the pursuit of beauty, order, symmetry, and proportion. This architectural grandeur mirrored the societal values of democracy, philosophy, and a nascent scientific understanding that characterized the Golden Age of Athens.

Contrast the classical beauty of Ancient Greece with the degrading and intentionally demoralizing simplicity of totalitarian societies. Communist architecture, especially the Brutalist style proliferated throughout the Eastern Bloc, stands as a stark symbol of the ideologies that shaped it. Devoid of innovative spirit, frivolity, and human scale, with a focus on raw concrete and functional form, it epitomized the state’s overpowering reach into the lives of its citizens. The colossal, austere buildings symbolized concrete edicts of power, designed to dwarf the individual and suppress any spark of rebellion or creative dissent. These buildings were functional in utility, but metaphorically they were monolithic declarations of a society that traded aesthetic beauty for homogeneity of thought and behavioral control.

Creativity and architectural innovation were not just stifled but were considered superfluous or even a threat, as they represented a past that had to be erased. The pervasive sameness of Brutalist structures across the Communist world mirrored the enforced equality where individualism and personal freedom were curtailed, and traditional or classical influences forbidden. They were the structural representations of an oppressive system, their very design anathema to aesthetics, attractiveness, and imagination.

Springsteen’s opening remarks in German, “I’m not here for or against any government. I’ve come to play rock’n’roll for you in the hope that one day all the barriers will be torn down,” set the tone for the event. Songs like “Chimes of Freedom” and “Born to Run” became anthems for the audience, emphasizing themes of liberation and escape from communist oppression.

Moving from the contrasting artistic cultures of two opposing civilizations into the realm of music, the Baroque era brought forth a complexity and grandiosity that echoed the absolute monarchies of its time. Composers like Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel composed works that were complex and magnificent, often commissioned by and performed in the courts of the German States and England. Their music, rich in emotional depth and structural intricacy, resonated with the splendor of the architectural marvels of their time, such as the Baroque palaces of Potsdam and Oxford. These compositions, much like the grand edifices that housed their premieres, were a testament to the cultural ambitions and the elevated status of their noble patrons.

The Church was still a prominent influence on musical composers of the time. In the role of patron, the Church commissioned works while simultaneously providing a crucial performance space with stellar acoustics, shaping the sound of sacred music, and creating an environment where the auditory experience was as much a part of worship as the liturgy itself.

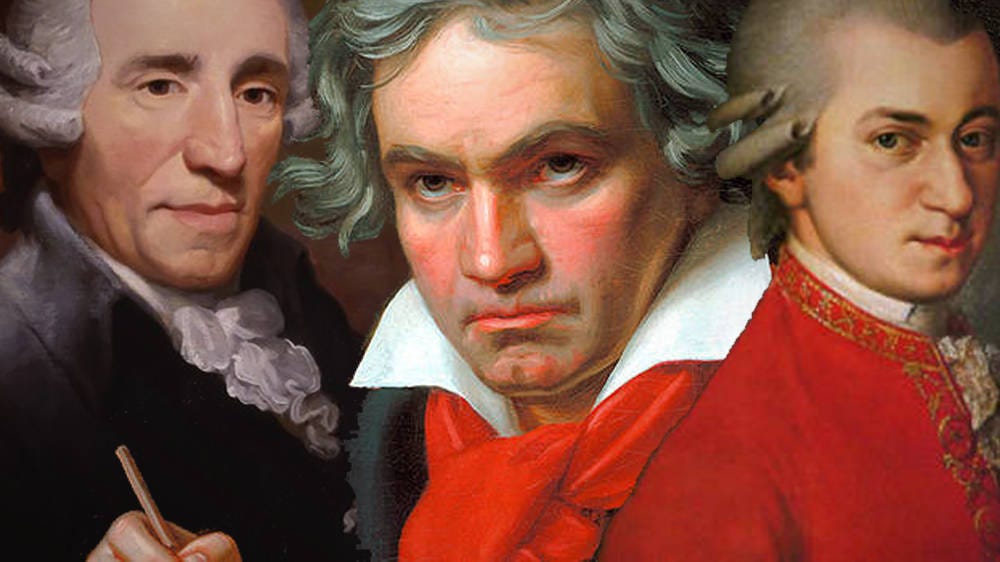

In contrast, the Romantic period of the 19th century was marked by a musical revolution that sought to emancipate emotions from rigid rules of social conformity and highlight the individual. Composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven broke through the structured elegance of the Classical era to unleash a passionate and often tumultuous expression of the self and the sublime. This was music that sought to reflect and amplify the human spirit in an age that was grappling with the transformative consequences of enlightenment thinking, and economic growth through the Industrial Revolution, as the peoples of Europe began to question the legitimacy of hereditary monarchies that were dominant for the prior millennia.

The classical era gave way to new forms of musical expression, with new instruments capturing sounds for innovative genres. Amidst the tapestry of cultural expression, the blues emerged as a raw and poignant articulation of the Black experience in the Deep South of the United States. Born from the fields and the hardships of slavery and segregation, the blues was a confluence of African rhythms and European harmonic structures, encapsulating the grind of a lost and outcast community. The melancholic twang of the blues guitar and the soulful depth of its vocals became the musical embodiment of the sorrow and hope of a singular common struggle. The genre was a profound vehicle for emotional connection and storytelling that would influence future popular genres.

Jazz, which sprouted from the seeds of the blues, soon blossomed into an eclectic and sophisticated language of music. It became synonymous with the Roaring Twenties and the defiant exuberance of the post-World War I era. In cities like New Orleans, Kansas City, and Chicago, jazz echoed the pulse of a changing America, with its improvisational nature capturing the era’s innovative spirit and the arrival and chaos of modernity. The syncopated rhythms and brassy serenades of jazz mirrored society in the throes of rapid industrialization and urbanization, offering a soundtrack to the turbulence and complexities of the evolving American psyche. Jazz was a cultural phenomenon that challenged often stifling social norms and encouraged a spirit of rebellion through improvisation and exploration.

The arrival of rock and roll in the 1950s conceived from the womb of Rhythm and Blues continued this legacy of music as a reflection of societal shifts. Rock and roll was the sonic emblem of youthful insubordination and a burgeoning counterculture. Artists like Elvis Presley, Fats Domino, and Chuck Berry became icons, their music resonating with the independent and economically vibrant rise of the middle-class youth of the postwar generation. Rock and roll music was inherently intertwined with the era’s social issues, from civil rights to the questioning of traditional authority and social conformity.

Its infectious rhythms and primal energy embodied the teenage zeitgeist, symbolizing the cultural revolution that would come to a head in the 1960s and 1970s. It represented a break from the past, much like the automobiles and suburban sprawls that were reshaping the American landscape, signaling a move towards a more open, and contested social order that dared to challenge the tyranny of government overreach through an ever-expanding American empire that, similar to the past twenty years, cared more about influencing other parts of the world through chaos and strife as “foreign policy” than the well being and prosperity of citizens of the homeland.

Musical genres, as diverse and rich as they are, can be incisive indicators of the cultural and moral compass of a civilization.

Punk rock which emerged in the 1970s to displace disco was the reacationary sound of raw discontent. It was a visceral response to what was perceived as a bloated and hypocritical establishment during a period of economic and social decay. This musical critique set to driving power chords, echoing a generation’s frustration with a society that felt uniform and unchanging, dark and sometimes hopeless. Perhaps the punk movement also sought to test the limits of extreme grime and overt shock, for the sake of evolving music culture along the paths that preceded it.

In stark juxtaposition, music from the classical period, composed by the likes of Mozart, carried the undertones of an ordered universe. Music was ornate, highly structured, and emotionally expressive. It valued clarity, balance, and form. It echoed Enlightenment principles of symmetry, rationality, and the pursuit of perfection. This was a time when society began to place a higher value on intellectual exploration and individual human potential, and the music of the period often mirrored these ideals with its structured elegance and harmonic simplicity.

Fast forward a few centuries to genres like Hip Hop and Rap and the reflection becomes starker. Apart from early Hip Hop and Rap, today these genres have reached their terminal stages, which always seem to arrive with indulging in the glorification of wealth and conspicuous consumption. The criticism here isn’t rooted in its origins or the race and class struggle its favorable critics insist gives its roots cultural value. Those roots have degraded into the celebration of wanton excess and pornographic hedonism. The repetitive and recycled nature of both Rap and Hip Hop rarely indulge creative exploration preferring to favor monetary extraction often at the expense of emotional depth and authenticity.

Reproduction and repetition of musical pieces that lack originality or any aspiration to manifest a genuine expression reflective of a greater human experience or understanding is rejected for the cynical monotony of flexing hyper-individualist desires in a post-modern world where material displays retain all social capital, and where art need not evolve or aspire to anything beyond capturing the attention and dollars of consumers. In many ways, it perfectly encapsulates the social rot and moral decay of present-day America.

Rock and roll, in its golden age, was also a musical revolution, and some made the same accusations of decadence and decay at the time of its emergence. Still, this revolution carried a sense of breakthrough rather than breakage, representing the vitality and energy of post-war youth. Yet, as rock evolved, it too began to mirror the excesses and abundance of the society from which it sprang, and by the 1980s embraced extreme depravity with the idolatrous hedonism of rockstars becoming almost as big as their hair.

The Alternative or Grunge subgenre sought to reject this hedonism through a repackaged individualism that was more sinister and indifferent and deserted money and riches, and their material representations as signs of “selling out” to the forces of corporate dominance that spent the same decade monopolizing nearly every industry, including musical production and distribution toward its final popular resting place.

Music has the power to be the soul’s mirror to society for any given decade, revealing through its shifting styles and themes whether a civilization is ascendant and aspirational or hopelessly demoralized and incessantly digging its own grave and anything in between.

Music has long been recognized as a potent catalyst for a common cultural experience, weaving individuals toward shared emotion and connection. The concept of “collective effervescence,” as described by sociologist Émile Durkheim, captures the essence of communal bonding that occurs during concerts.1 The live music experience acts as a conduit for this phenomenon, leveraging the mirroring capabilities of our neurons, which activate not only when performing actions but also when observing others.2 This neural mimicry can lead to “emotional contagion,” to describe the synchronization of shared feelings within a group.3

Studies on the neurochemical impact of music highlight how the shared experience can trigger the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to pleasure and reward.4 The physical act of moving in rhythm with others during a live performance also fosters a sense of unity and amplifies emotional states.5 This synchronization of movement and rhythm can deepen the connection between individuals, reinforcing the collective experience as trance-like and even hypnotic.6

Marshall McLuhan’s famous saying, “The medium is the message” argues that different communication mediums ( print, radio, television, the internet) have unique characteristics that shape how people perceive and interpret information. The medium influences the way people think and interact with the content.7

While his sentiment still stands, it applies more appropriately to media and information than the technologies transforming art and culture. McLuhan died in 1980 and never lived past the analog era to see just how greatly new mediums like the Internet and digital technologies would transform not just how people perceive and interpret information prepared for their consumption by powerful forces, but how they experience and engage with cultural products, especially music.

The arrival of the digital age greatly transformed how all culture was produced, promoted, distributed, and consumed, from music, and film, to millions of podcasts that nobody listens to, and finally to what you are reading here—a combination of academic and creative writing for the distribution of ideas.

Digital Interlude

Before we continue along to that technological point that transformed music, let it be known I have no misconceptions about the power of the Internet and the innovations that have sprung from this global network. In less than two years I have been blessed to build this Substack to a low five-figure readership with no promotion on Social Media, and no money allocated for marketing or advertising. The Internet, and specifically this wonderful community on Substack, free from censorship due to its subscription model, has made it possible to share my written thoughts with others. I’m still humbled that others are interested in reading my words. Should these particular words bring value to your life, I hope that you will honor me with your patronage, or share that value with others.

While the digital technological transformations may have democratized cultural production and accelerated access to distribution, bypassing traditional anointed gatekeepers of culture, often overly educated critics living in a few major metropolises, it has also had a deleterious effect on how society consumes music, obliterating the aforementioned connections that could only arise from synchronous consumption that births collective cultural milestones.

If the medium is the message with music, the technological medium that produces, distributes, and broadcasts digital music has delivered a message that this new system dilutes the human experience which conversely degrades any aspiration to produce great works. The new digital marketplaces that have democratized production and distribution, favor quantity and fractional payments that have killed the album experience and ushered in the singles era.

Musical production has atomized consumers, shattering any euphoric shared experiences into a million different movements with no singular genre standing as a bastion of accurate cultural representation. Perhaps that old Seinfeld adage—a show about nothing—is the only true barometer of this musical epoch.

The quality of a civilization’s culture is not always in direct proportion to how that civilization rewards cultural production, but a civilization that moves from enormous incentives for popular musical production to fractions of that within a matter of years, will disincentivize and thereby decrease the pool of viable producers.

For example, when teenagers were asked what they wanted to be when they grew up in the United States in the 1960s through 1990s, many would have responded in that predictably superficial way only a mass consumer society that worships money and celebrity would—as a rock star.

Fast forward just one generation and the money and celebrity haven’t changed, but the superficial aspiration has morphed into something far more shallow, requiring no talent, charisma, or creative spirit—a YouTube star.

At least the former was rewarded much greater, had to leave home to work (tours), and knew how to play musical instruments and write songs that captured the imagination.

Today the YouTube streamer steals the music produced by yesterday’s rock stars while doing nothing that adds anything of value to the culture while talking to someone called “Chat.” There is no human connection between those viewers experiencing this stream of nothingness. Any interesting or revolutionary ideas from “YouTube Stars” are more likely to result in censorship, demonetization, and expulsion from the platform.

From Royal patronage commissioning court composers to the phonograph, radio, vinyl, 8-track, cassette, and compact disc, to where we are today, musical compensation of artists peaked in the 1990s, and while the democratization of production and distribution has allowed for greater participation in musicians accessing fans, the amount of compensation has plummeted to indecent poverty, even at the top tier. There is no way to effectively gauge how much the digital transformation of musical distribution has pilfered from musical artists via copyright infringement through outright piracy.

Compare the radio compensation model of the 1950s to the streaming compensation model of corporate tech monopolies. Let’s say Elvis’ Heartbreak Hotel was played 4x per day on roughly 500 national radio stations at the apex of its popularity. That’s 60,000 plays per month at a minimum of .04 cents per play, which came to $2500 per month. If Radiohead’s song Creep is streamed ten million times per month nearly thirty years since its release at a payment of .00034 cents per stream or sometimes nothing, with no transparent ledger of accounting besides the word of Silicon Valley thieves, it pays the band $3400 in today’s money.

Adjusted for inflation Elvis made $24,000 from radio play in today’s dollars, and there was no way anyone could pirate his music with replication technologies. He made even more through vinyl sales. Creep has probably been stolen tens of millions of times through digital piracy costing each band member millions of dollars, but according to digital age accolytes they’re supposed to be grateful that their music is being stolen because it helps them “find a new audience.”

This brings us to the defining techno-social differences affecting culture and musical consumption in the digital versus analog era.

Analog: synchronous and symmetrical | connected and shared

Digital: asynchronous and disparate | disconnected and shattered

This shift created an atomized music culture while dispensing all shared connections music once supplied. Much of our twenty-first-century world has robbed humanity of shared experiences—a glue that undergirds social cohesion and togetherness.

In the 1980s lines would form around the block of every Tower Records in the United States when a popular artist released a new album. The promotion and music videos released in advance of the album created a buzz. Friends would line up together, purchase a cassette or Vinyl, sometimes both, and then maybe return to someone’s home, or sit and park and listen to the album on cassette in a car—together.

Today nobody gets together to acquire musical works of any genre. Everyone is alone, clicking a “buy” button, or running their piracy torrent software to steal from musical artists.

If every individual is fragmented and isolated to experience their own thing alone—usually tinny-sounding digital singles—then the music culture is simply that Seinfeld irony—nothing at all.

To be clear there is a popular music culture in the twenty-first century, but perhaps it represents no culture, signifies no struggle, aspires to no greatness, breaks no barriers, defies no authority, communicates no beauty, connects no society, shares no wisdom, and imparts no flattering reflective commentary on our world, only the aforementioned rot and decay, debauchery and hedonism.

It’s as if, sometime at the turn of the century, when the digitally disconnected transplanted the synchronous and analog, all those decades of great popular music that poured into the cultural consciousness binding society through shared creative experience, were all at once, suddenly, shut off at The Spigot.

As a graduate student and later a PhD researcher at one of the oldest universities (Jagiellonian University, 1368, Kraków, Poland) I was lucky to have an academic supervisor who is a Professor of Sociology and Cultural Studies and teaches a course on Music culture.

Born in a working-class borough of South London, Professor Garry Robson came of age during one of the greatest periods of popular music—the 1960s and 1970s and experienced first-hand the bands of the British Invasion before and after they invaded America.

A few times each year a different person in our small circle in Kraków hosted a YouTube party, which had nothing to do with YouTube and everything to do with embracing the platform’s last ounce of usefulness—listening to music and watching old music videos, together, as a shared experience. These gatherings lasted sometimes late into the morning hours, without anyone noticing. The keyboard moved around the room and each person chose one or two songs before it reached the next person and so on.

While the surface goal was to experience great music together, in a social setting, it also became a kind of game, of throwing off the others, of shifting the trajectory toward something unexpected yet very much a splendid surprise. Instead of a single DJ curating a musical set, we were four or five DJs curating a musical experience with spontaneity and serendipity.

While any music was fair game, for every fifty songs chosen from the 1950s through the 1990s there was maybe one song chosen after the year 2000, and it usually involved an artist that ascended in a pre-Y2K decade.

One early morning at my flat, a few hours before sunrise it was just Professor Robson and I refusing to allow the music to stop, passing the keyboard wirelessly connected to the TV back and forth when I asked the obvious question— “Why after decades of consistently great music does most music suck after the turn of the century?”

He mentioned the Spigot, and how at some point “they shut it off.”

I re-ask the Good Professor this question in Episode #3 of Good Citizen Radio Bleats “The Spigot,” so tune in to hear his thoughts on why he believes this happened.

The absence of the power of a shared music culture to bring people together today (outside of concerts) signifies a profound loss that millions of people, particularly of older generations, deeply sense but cannot accurately understand or describe.

They only know that at some point the music stopped, and the spigot was closed.

A society that has nothing new or innovative to offer in terms of music culture in the present will see generation after generation constantly looking to the past, either out of inspiration, or nostalgia.

They will seek out music that once represented a culture, signified a struggle, broke down barriers, aspired to greatness, defied authority, communicated profound beauty, connected people, shared wisdom, and imparted some reflective commentary on a world that was less anesthetized, less demoralized, more dynamic and vibrant, one that they wish was still around but will never return.

Perhaps that’s our music culture now—reliving the glory of past music cultures and sharing it with others.

And that’s why I add at least one song to compliment every post here.

Immortal Beloveds, ever yours, ever mine, forever.

Thank you for sharing

Visit shop.thegoodcitizen.live

1. Use your affiliate link for either Healing Support promo or for Heartmend promo.

2. When the customer enters the floralive site (thru your link) they must add EITHER

A. add 3 Healing Support (combination essence) and 3 Blue Eyed Grass to the shopping cart, then go to checkout and enter the coupon code for this promo which is: HSHOLIDAYS (not case sensitive).

This will charge them for the Healing Support and they will get the Blue Eyed Grass free

Or

B. Add 6 Heartmend to shopping cart, go to checkout, there will be a charge for 4 Heartmend and two free when the coupon code HMHOLIDAYS is used.

![]()